Will the North American Leadership Summit Result in Substantive Immigration Policy Change? By Sunita Sohrabji

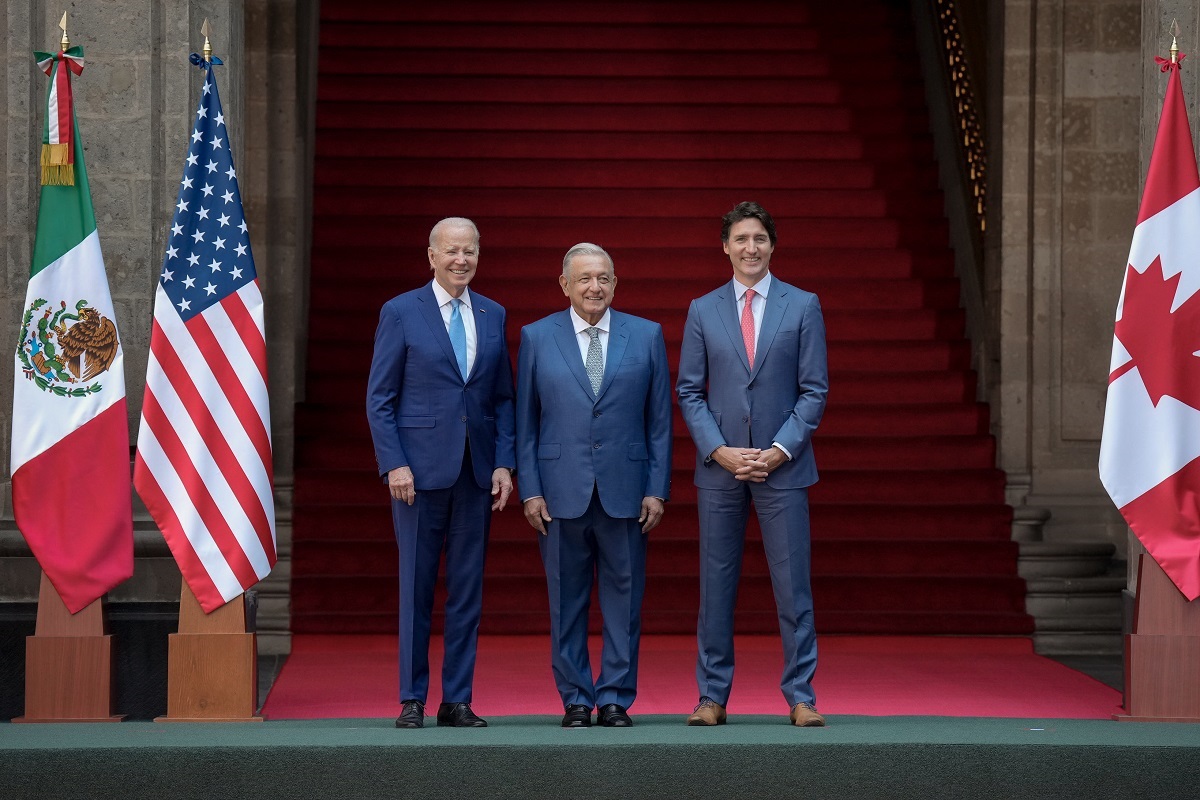

Sweeping changes in immigration policy — including the immediate revocation of the Trump-era Title 42 policy — were promised by candidate Joe Biden on the campaign trail. Two years later, however, the policy has not been revoked. President Biden last week announced harsher restrictions on migrants attempting to cross the US-Mexico border without requisite immigration documents. The announcement came ahead of his visit to the US-Mexico border and his meeting with Mexico’s President Andrés Manuel López Obrador and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau Jan. 10 afternoon in Mexico City.

The three leaders discussed a wide range of topics, including immigration, climate change, economic policy that would encourage migrants to remain in Mexico, and the trafficking of the opioid drug fentanyl, among other issues. As expected, immigration dominated the discussion.

“This is the moment for us to determine to do away with this abandonment, this disdain and this forgetfulness for Latin America and the Caribbean,” López Obrador said Jan. 9, ahead of the meeting.

As Biden and Trudeau met with Lopez Obrador, Ethnic Media Services sat down with Ariel Ruiz Soto, policy analyst at the Migration Policy Institute to discuss the summit. Soto works with the U.S. Immigration Policy Program and the Latin America and Caribbean Initiative.

His research examines the interaction of migration policies in the region that stretches from Panama to Canada, as well as their intended and unintended consequences for foreign- and native-born populations. Here are highlights from the interview.

EMS: What were your top priorities for this summit?

ARS: There’s a few things that we’ve been following that have been really key leading up to this event. One of them is understanding what’s the Mexican strategy on migration enforcement going forward. What could happen from this if for example, Title 42 is continued and Mexico decides to continue accepting expedited removals from the US to Mexico. Under what terms and for how long should we expect?

The second component is specifically looking at Mexican reforms on not only visas or on US visas and pathways not just from Mexico to the US, but also from Central America to Mexico. Mexico had committed to providing increased access and legal pathways to Central Americans in that country.

On the Canadian front, we want to know the new commitments by the Canadian government to accept refugee resettlement from Central and Latin America. Canada has actually committed to increasing refugee resettlement by between two and 10%. But those really tend to be small numbers and obviously for all of Latin America, a very significant geographically large region, it may come down to hundreds or small thousands by country.

Investing in Mexico

Finally, what about investment in the region? When the Biden administration came into power, there was a big call to try to rejuvenate efforts in investment in the region to address the root causes of migration.

But it seems like that priority has gone to the back burner and now more issues about control and enforcement have taken the forefront in that discussion. But ideally Mexico, Canada and the US had already suggested plans to invest and provide resources for the most devastated communities.

Now those are the big aspects of what we would expect to come out of this. What we have seen from the White House readout and press on this is more general commitments to continue discussions but also to continue advancing principles, including some that have been already identified under the Los Angeles Declaration.

EMS: What concrete developments lie ahead?

ARS: One of them is the announcement of creating a virtual platform about the legal pathways that there are to migrate into the United States and Mexico and Canada. This announcement of a virtual platform between the three countries to look at the legal pathways…is not going to be the solution to the flows at the border, but it will create some order, specifically for some groups that would otherwise venture to risk their migration journey through a smuggler.

Then there’s another development: creating a new center in southern Mexico to talk about access to legal pathways and partnerships with Mexican private sector support. It’s essentially trying to connect migrants, or would-be migrants to economic options for them to consider staying either on the Central American side of Guatemala or in Mexico before attempting to continue northward.

This is not a new strategy, but it’s a good one. Private sector should be more involved.

EMS: Does Mexico have the resources to absorb the massive numbers of migrants it now has to house and shelter?

ARS: Clearly Mexico doesn’t have the resources available to integrate the migrants that it receives from the United States. It doesn’t have the shelter capacity in Mexico. Most of the shelters are run by civil society organizations and mostly through humanitarian programs or church affiliations.

But many migrants who are going to be expelled to Mexico are probably not going to stay in Mexico for a long term, specifically if they are Cubans because they have family connections, networks, and reasonably sized financial access to diaspora in Miami and other places in the United States.

They’re most likely to try to enter multiple times. Title 42 expulsions mean that there are no consequences in processing for migrants, and therefore they can try four, five, six or seven times, just as Mexicans do today.

Venezuelans

Venezuelans, on the other hand, have very little knowledge of the US. They have some family ties but not many. And after going through a significant journey, many of them just are frustrated and tired by the process and want to return home.

So the question that you ask has two parts of it. One of is does Mexico have the resources? No. But I don’t think migrants that are being expelled to Mexico to begin with would want to stay there anyway.

Ken Salazar, the US. Ambassador to Mexico, has said there will be about $23 million provided to shelter organizations on the Mexican side of the border. That’s a good development, though I would have questions about how that will be disbursed and what requirements will be mandated of organizations receiving the disbursements.

EMS: President Biden announced Jan. 5 the continuation of Title 42, with harsher penalties for migrants attempting to enter the US without papers. The proposal also allows 30,000 migrants from Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua and Haiti to enter the country each month as part of a humanitarian parole program. How would you characterize the policy changes?

ARS: Let’s be frank about this. Even 30,000 people per month is not enough to contain the flows or to receive the flows that are arriving at the Mexico border when we’re seeing upwards of 70,000 per month.

But the US. Immigration system doesn’t really have any other tools to provide control enforcement at the border right now that would apply to these hemispheric flows. It doesn’t have enough ability to return migrants to the other countries, even directly under regular removal.

And parole — while it is an important tool — is not sufficient in the long term. Parole does not necessarily mean that people, after the two years that they are given to come into the country, will actually have a meaningful way to stay. That has not been the case with Ukrainians. It has not been the case with the Afghan migrants, and it may not be the case for Venezuelans, Cubans, Nicaraguans and Haitians.

Title 42 is Not Sustainable

In the announcement last week, President Biden was trying to figure out how to ignite a more cohesive response with Mexico and Canada so that short term measures actually give and buy some time for the longer outputs. But I don’t think anybody believes that Title 42 expansion is sustainable, not just because of the courts, but also because the flows are continuing to change. We are seeing increasing numbers of Colombians, Peruvians, Ecuadorians: it would be unrealistic to believe that expanding parole to Peruvians, Colombians and Ecuadorians would essentially be the solution to everything we are seeing at the border.

EMS: What does humane immigration policy look like? And given the very divided House and Senate, can we expect to see that in 2023?

ARS: Humanitarian approach to migration by the Congress would entail improving access to asylum first and foremost, and second, providing more resources for the organizations and communities that are most impacted by the arrivals of migrants to the US-Mexico border, but also in the interior. I think we’re far from that reality.

Unfortunately, the Republican-led House, and the Democrat-led Senate are likely going to be in a stalemate when thinking about what to do in terms of providing humanitarian access. We’ve seen this before. It’s not new.

Republicans usually refuse to talk about anything on immigration until the border is secure. And there’s not really a definition of what secure border means, unfortunately. And then the Democrats many times rely only on regularization and providing benefits to migrants rather than also considering options to improve control at the US-Mexico border. So that tension and stalemate will continue.

Increase Resources at the Border

Now, that doesn’t mean that there may not be smaller pieces of regulation that could actually work together. Democrats and Republicans agree that there has to be better technology to screen and process migrants when they come to US-Mexico border. They both agree on increasing the number of Customs and Border Patrol officials as well as US immigration agents, and immigration judges. And both agree that the capacity for shelter and detention capacity as well as resources and technology is severely underfunded at the US-Mexico border.

Those are things that I think they can agree on, but they tend to be secondary to each of the party’s top priorities and therefore lead to stalemate.