Exodus Lending: An escape route for victims of predatory loans

By Khalil Abdullah, EMS contributor

Recurring utility bills, rising rents, and now the specter of inflation, often make the ubiquitous and easy availability of payday loans – instant cash in one’s bank account – too enticing to forgo, despite their exorbitant interest rates.

But thanks to the work of a Minnesota non-profit, residents now have a way out of the cycle of predatory payday loans.

“It is a myth that payday lending thrives on unforeseen emergencies,” explains Anne Leland Clark, executive director of Exodus Lending. “We have Pew Research Center data that 69 percent of payday loans are used for utilities, food, and rent. Even more telling, about 75 percent of payday lender fees are generated by people who borrow for 10 consecutive two-week periods or longer.”

Clark spoke at a Federal Trade Commission forum on consumer scams hosted in Minneapolis by Ethnic Media Services. While scams, by definition are illegal, she expressed interest in collaborating with the FTC to address the legalized immorality of the payday loan industry.

Pioneering a reimagined world of consumer lending in Minnesota, Exodus Lending offers an alternative to financial servitude and the debilitating emotional toll of missing a payment that accelerates a cycle of spiraling debt. Exodus clients are not seduced to enroll in the organization’s programs by promises of prosperity, but rather seize the opportunity to attain respite and relief.

Granted its non-profit status in 2017, lending began in 2015 as a program of the Holy Trinity Lutheran Church in Minneapolis. Since 2015, over 500 customers have been enrolled; 386 have fully graduated the program debt free. There is, however, a $1,500 dollar limit for a customer’s loan indebtedness.

“We step in and take over the loan,” said Clark. “We pay off the lender in full and then restructure the debt as an interest-free loan over 12 monthly payments.” Additionally, Exodus reports those on-time payments and successful pay-offs to credit bureaus, thereby building customers’ credit worthiness.

Clark noted that, with a small staff monitoring clients’ needs, Exodus Lending has the capacity to adapt fairly quickly to market conditions. The number of applicants declined during the peak of Covid in 2020 and 2021 as federal and state monies poured in to subsidize business payrolls and assist renters with monthly payments. Moratoriums on student loans eased pressure as well, but in the current fiscal landscape, with less federal funds available for the public, Exodus opted to raise its loan cap from $1,000.

In the strict definition of a payday loan, borrowers agree to pay off the entire loan, plus interest, on the following payday, be it monthly, weekly, or bi-weekly. “In many cases,” Clark explained, “borrowers take out another payday loan to pay off the initial one. They get in a debt cycle of reborrowing and rolling over the loan and adding fees every time.”

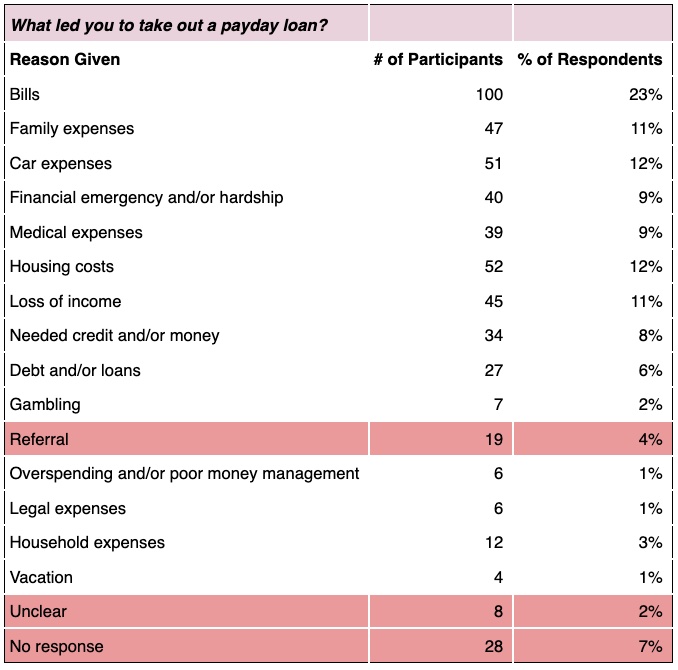

Data from Exodus Lending, representing roughly 500 individuals who have gone through the program.

It is not uncommon for borrowers to have a mix of loans, for example, by securing a high interest rate installment loan for funds to cover payday loan costs. “Nineteen states and the District of Columbia have passed a 36 percent interest rate cap on lenders’ interest in their states, and, unfortunately, Minnesota has yet to enact proposed legislation that would do the same. But regulating on-line and out of state lenders is challenging,” Clark said.

Those lenders, including some Native American tribes, aggressively market their services across state lines on social media platforms. “All that’s needed is for the customer to have a debit card and access to the Internet. But the customer is also giving up personal banking information and, of course, permission for the lender to deduct the payroll deposit.” That access may result in money being pulled from an account arbitrarily.

Clark said in some cases, Exodus will step in and take over several loans for a single customer if the combined loan total is within the Exodus cap. For instance, a customer may have two or three $300 installment loans to try to make up the shortfall needed to make a payday loan payment. Exodus will pay off the ones within its lending cap, initiate its own program discipline and then refer the customer to Minnesota Attorney General’s office or Minnesota’s Department of Commerce to deal with the balance.

Clark lauded both entities for their attentiveness and commitment to consumer advocacy. “Keith Ellison, our attorney general, has been one of our champions. His office and Commerce have been great. Sometimes they call the lender, and say, ‘Hey, the principal has been repaid, why not close this off your books?’”

For over 10 years, Clark worked at another Minnesota non-profit, Prepare and Prosper, where she developed, implemented, and led programs designed to foster financial health, including free tax preparation for Minnesota residents. “We worked closely with Exodus and I had served on its board for three and a half years, so the opportunity to serve as executive director was like coming home.”

Only in the executive director’s seat since February, Clark is optimistic about Exodus Lending’s future and opportunities to share its methodologies with other non-profits, community service organizations, and religious institutions. She noted that some synagogues have Jewish free-loan societies that function in a similar fashion.

As a long-term goal, Clark envisions Exodus as a primary lender competing head-to-head with payday loan operations.

“We’ve received a grant from the Treasury Department and we’re exploring becoming a Community Development Finance Institution, which is a federal designation. CDFIs are beginning to step into this lending space where in the past funds have been directed more toward housing and other program objectives.”

At present, Exodus receives foundation grants and donations to cover salaries and overhead, but also garners revenue from private donors.

“Over 50 percent of our budget is supported by individuals, many from the faith community. We have donors who contribute $10,000 to $25,000 for as long as three years,” Clark said, “and charging no interest for the use of those funds. Those funds constitute the core of our lending pool.”