Redistricting hearings redefine what “public” means–Alabama and Georgia a case in point

Redistricting hearings redefine what “public” means–Alabama and Georgia a case

in point

By Khalil Abdullah, Ethnic Media Services

If Alice in Wonderland were set in Alabama, Felicia Scalzetti could play the lead role. “The

question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.” For

Felicia in Alabama’s Wonderland, the question is, does “public hearings” mean the hearings are

accessible to the public?

“So, we have 28 public hearings and 27 of them were between 9am and 4pm,” recounted

Scalzetti. “Some of our biggest cities had their hearings first thing in the morning, 9am to 11am

during weekdays.

“Think to yourself, what Alabamian is available to drop everything, drive to a community

college, figure out what building they’re supposed to be in, and then stand up and testify when

we don’t know what the agenda is for that meeting and it’s occurring at 11 am on a Tuesday? It’s

not accessible.”

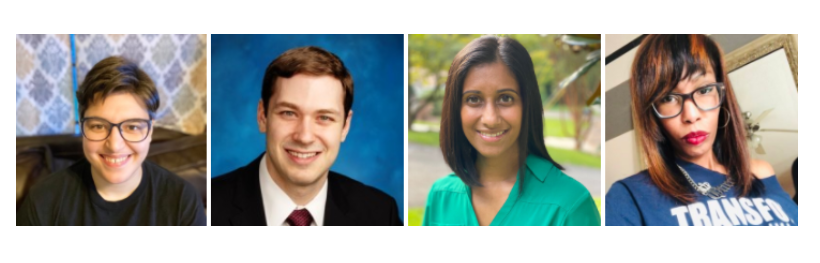

Scalzetti, a Redistricting Fellow representing T.O.P.S. (The Ordinary People Society) and the

Alabama Election Protection Network, participated in a media symposium on redistricting

sponsored by the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Redistricting occurs after every decennial census. It comprises drawing new maps for

congressional, state, county, and even school board districts. These maps must ensure

proportional numerical representation for congressional districts, but also should seek to

maintain the integrity of a state’s respective communities. A community of interest, a concept

under federal law, may be defined as an ethnic or language group, for example, or even those

who share geography, such as a rural district.

A handful of states have independent or non-partisan commissions, presumably to foster

impartiality in drawing new maps. Alabama and Georgia are among the majority of states that

consign the legislature to handle the task. The result is typically an exercise of raw political

power.

The numerically dominant political party appoints members to a redistricting committee, which

then sets the agendas, places, and times of hearings, as well as criteria for what and whose

testimony will be considered.

Historically, Alabama and Georgia’s Republican-controlled legislatures, have disenfranchised

African Americans and minority voters, in part, by how district lines are drawn. The Supreme

Court has held that redistricting by race is illegal but ruled that redistricting to benefit a political

party is not. However, as most African American voters tend to be Democrats, the negative

impacts of legal “political” redistricting on minority communities occur with regularity.

“We are very concerned that the political maps that emerged from these sham processes will

break up and dilute the voting strength of communities of color,” explained Jack Genberg,

Senior Staff Attorney, SPLC.

“Packing” occurs when maps are drawn that circumscribe the majority of an ethnic group

within a single district and thus reduce the number of congresspersons it could elect.

Conversely, “cracking” carves a community into segments, placing each within a district where

its members will be outvoted by a numerically larger community that has a different political

agenda or aspirations.

“We have seen similar tactics to dilute the voting strength of people of color repeated over and

over in the recent histories of Georgia and Alabama,” Genberg said. “When communities of

color have access to fair and equitable representation, they ultimately are able to secure their fair

share of resources and improve schools, rebuild roads, and provide better health care.”

Based on a state’s per capita census population count, billions of dollars pass from the federal

government to fund programs in each state for the ten-year period until the following census.

Often elected officials – directly or indirectly– determine the funding priorities within those

programs.

Karuna Ramachandran, Director of Strategic Partnerships, Asian Americans Advancing Justice,

expressed her frustration with Georgia’s redistricting committee, She cited its lack of

responsiveness to requests for information about the criteria to be used to draw new district lines,

its failure to include recommendations from the hundreds submitted by residents from across the

state, but also for its notable failure to deliver information on redistricting in multiple languages.

“We’ve challenged the fact that this entire process has been conducted in English only,”

Ramachandran said. “We have a growing community of new Americans here in a state where

English is not the primary language and so that effectively just denies access to a huge

percentage of Georgians.”

Dr. Adia Winfrey, founder of Transform Alabama, said her organization has a statewide presence

but has devoted considerable attention to Talladega County where she is based.

“Our county which had previously just been within state senate district 11 was divided into four

senate districts for one county,” Winfrey said. Simply put, the African American community had

been “cracked,” with the result of lessening its collective voting power.

Winfrey said that there was a positive outcome of litigation in 2017. “The lines were redrawn. So

now we just had three districts, but that was still way too many, because we really don’t have

[fair] representation.”

As did Ramachandran, she stressed the benefits of individuals being given the opportunity to be

heard, the broadening of the public’s understanding of redistricting and other aspects of civic

engagement.

“Just looking for information that we could share with our communities… of wanting them to

understand the power of their story, and the power of them sharing their experiences – good and

bad – with their elected state house and state senate representatives… it really allowed us even

as a community to get a better understanding of how these lines affect our day-to-day lives.”