One man’s view of an ‘Upside-Down World’

One man’s view of an ‘Upside-Down World’

Clyde Prestowitz’ The World Turned Upside Down is the first major book on US-China relations to be published in 2021. The book, as stated by the subtitle, is about “America, China, and the Struggle for Global Leadership.”

For the author’s response to this review, click here.

Prestowitz’ first book was Trading Places, published in 1988, about how America ceded its future to Japan and how to reclaim it. He has written quite a few books since then, but in a sense, his latest book is Trading Places redux, except that China has taken the place of Japan.

More than 30 years ago, Japan was “stealing” manufacturing jobs from America. The author proposed certain strategies for the US government to negotiate with Japan and thus rectify the trade imbalance and bring manufacturing back.

Japan was a much-feared juggernaut back then. The venture capital community in Silicon Valley was so intimidated by Godzilla, they always asked, “Can Japan steal our ideas and make the widget better and cheaper?”

The venture capitalists basically stopped investing in electronic hardware ideas and emphasized the software side of technology. This mindset led to the emergence of fabless giants such as Nvidia, a company that has no manufacturing capability but is worth much more than Intel, which has billions invested in semiconductor manufacturing.

Before Washington could adopt some of Prestowitz’ ideas and move against Japan, Japan’s bubble economy popped. One could probably predict that this was inevitable when the Tokyo Palace grounds became more valuable than the total real estate of the entire US state of California.

But manufacturing did not come back to America. Japan hung on for as long as possible, gradually losing production to South Korea and some to Taiwan and eventually to China. Prestowitz blamed China’s entry to the World Trade Organization, after which it gamed the system and took unfair advantage of favorable terms to build its manufacturing base.

Before presenting my disagreements Prestowitz’ new book, I need to acknowledge that this is a valuable work, comprehensively researched, written with clarity, and full of teachable content.

Reliance on mercantilism

In the book, Prestowitz accuses China of rampant theft of intellectual property as an essential component of its economic rise. But he is fair-minded in that he outlines how every developing economy, including Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, “borrowed” ideas, design and technology from others to boost economic development.

Most interesting, at least to me, is how the United States under the leadership of Alexander Hamilton relied on systematic theft of technology from Europe, and the practice of mercantilism to protect the infant industries at home until the domestic manufacturers could compete with its foreign competitors.

Thanks in a large part to these mercantile policies, the US was to experience unprecedented economic growth. The book notes, “Between 1820 and 1870, the US GDP growth was, like China’s today, the wonder of the world.”

I have not read anywhere else as thorough explanation of what mercantilism is and how such practice can benefit the practitioner. Heretofore, I thought of “mercantilism” as a swear word to sling at another country if we don’t like its trade policy. But Prestowitz makes a convincing case that mercantilist policies are important to nurture infant domestic industries.

However, I have trouble with the two basic assumptions the author used to make his case against China.

First of all, Prestowitz appears to echo the zero-sum view of US-China relations popular among the denizens inside the Washington Beltway. Regardless whether American politics is from the right or left, they all assume that China is out to push the US aside and take over as the global hegemon.

US can’t stand being overtaken by China

The prospect that China’s economy will overtake the US seems to drive these Americans to distraction. To them, size really does matter and China’s growing economy causes a deep-seated sense of insecurity and an inferiority complex. While they stew in paranoia of their own making, they find no comfort in the fact that per capita income in China will take decades to catch up, if ever.

Depending on who’s counting, we Americans have around 800 to 1,000 military bases encircling the globe and we get upset and alarmed because China may have two. China’s first in Djibouti on the Horn of Africa was established to support the PLA Navy in its anti-piracy patrols. I don’t even know where the second is supposed to be, but how dare China challenge us with two international harbors?

Then in recent years, China has had the temerity to militarize atolls in the South China Sea. How are we supposed to exercise the freedom of navigation in that body of “international” water and not feel threatened by the menacing missile batteries? Our naval vessels sail with the best of peaceful intentions, but the Chinese guns pointing at the ships clearly do not.

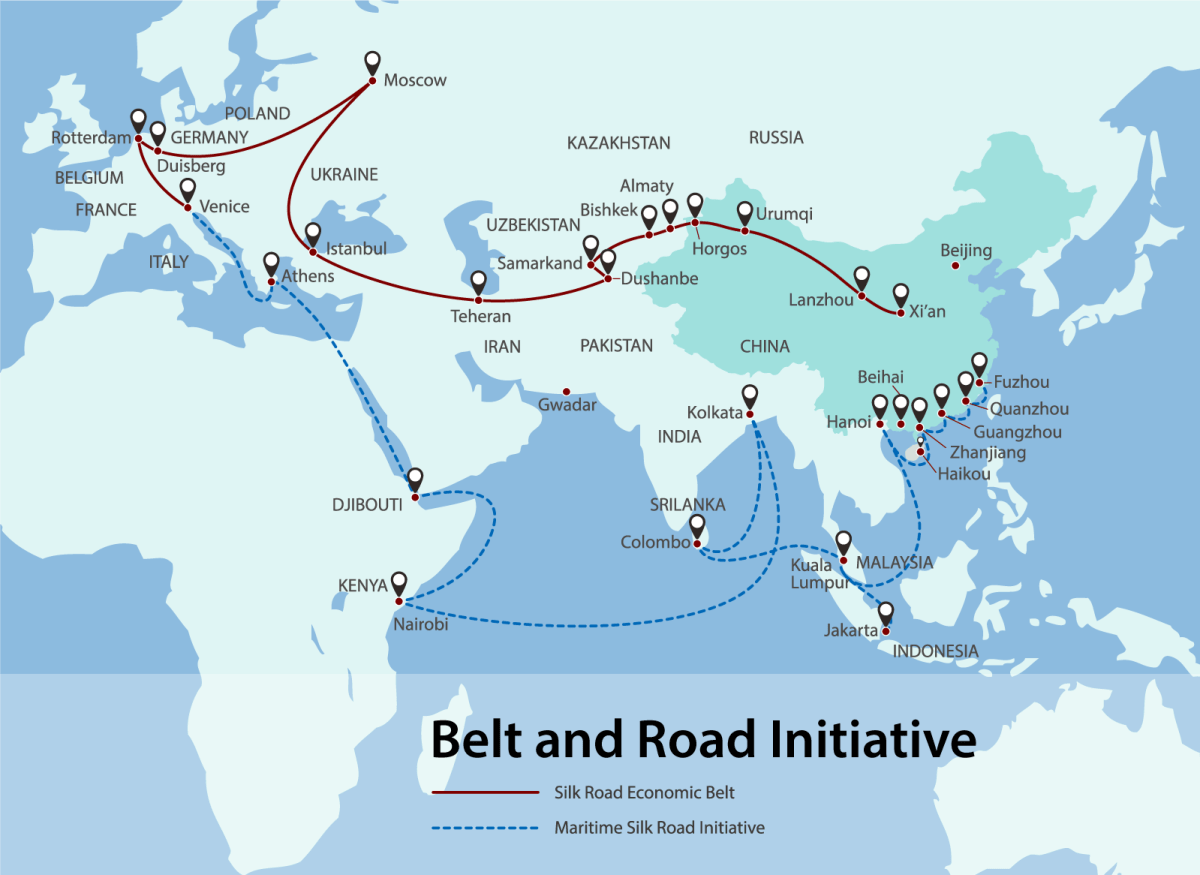

Overlooked in such recriminations is that China simply does not play by the same rules as the US. China has never acted on or expressed the desire to become the world’s No 1 military power. Its most powerful diplomatic tool is the Belt and Road Initiative to help other countries build their infrastructure.

To his credit, the author does not smear China by calling the BRI a debt trap or another form of colonial exploitation. While many in the mainstream media do step over the line and without any basis accuse China of gross misconduct, at least Prestowitz refrains from doing so.

Rather, he thinks it was clever of China to come up with the idea. “It broke no international rules, attacked no one, and alienated no one while attracting bevies of supporters and partners. At a stroke it made China into a major world power whose influence in some ways surpassed that of the US.”

In fact, China’s frequently repeated mantra is “win-win.” The best example of its practicing of what it preaches can be seen in a documentary from Singapore on Uzbekistan as the “buckle” of the BRI.

BRI offers growth prospects

The excitement in Uzbekistan is palpable as China build high-speed rail to connect the double-landlocked country to the sea and to the rest of the world. Uzbek officials now talk about the prospects of an economic boom that could replicate what happened to Japan and China.

China offers access to its huge market and its inbound investments create massive employment opportunities. The Chinese in Uzbekistan and the Uzbeks are open and cordial with each other. Both sides win and there is no recrimination or talk of mercantilism.

The second reason that Prestowitz considers China a bad actor is that the country is run by a one-party system, and what’s worse, a Communist Party at that. This is true. China calls it a socialist party with Chinese characteristics. Apparently, the author does not like that label, preferring to call it a Leninist party. I am not sure what that means, but I am certain it’s not good.

Prestowitz accuses the Communist Party of China of oppressing the people, denying them personal freedom and certainly freedom of speech. Ever since China “conned” its way into the WTO, it has made tremendous economic advances. But from the author’s point of view, all the benefits went to the CPC and very few to the people of China.

When the folks in Washington call out “communist” China, it says it all. This epithet justifies all the bad things we can ascribe to that country – even when China has systematically lifted millions out of poverty every year until can now claim that no one is left behind.

The author lists Hong Kong, Tibet and Uighurs in Xinjiang as evidence of human-rights abuses in China. My disagreement is too complicated – and enormous – to go into except to say that he is unduly influenced by a small handful of vocal dissidents given a huge megaphone by the mainstream media and actively supported behind the scenes by the National Endowment for Democracy.

(I gave one example of deliberate distortion by the mainstream media in a recent Asia Times article.)

The book is critical of China for the lack of freedom of speech, an accusation that is more off than on the mark. The Internet-savvy generations in China exercise plenty of free speech criticizing policies they do not like and posting videos of misbehavior by corrupt officials. Government officials monitor the Internet carefully because that’s a critical source of public opinion that they have to listen to.

‘Inferiority’ of China’s one-party system

It’s true that China does not let free speech run wild like in the US. Not a day goes by here without some politicians spouting nonsense. The media have lost their integrity in order to survive financially and can’t help the public distinguish the real from the fake news.

It’s also not clear that China’s one-party system of government is inferior to our two-party system. Party members in China on track to become officials are graded and measured every step along the way, from the local to city to provincial to national level. They have to prove themselves capable of discharging their duties before they can move up.

What do we Americans use as meritocracy to select our leaders? Would-be politicians need to be rich or have access to wealthy donors. Money trumps – excuse the expression – competence, rhetoric and public persona outrank one’s track record, experience or accomplishments. Each political party is more interested in suppressing the other than getting anything done for the public good.

In the case of the US competing with Japan, Prestowitz’ proposal was for a proactive federal government to take counter measures and negotiate limits for Japanese economic expansion into the US. To counter China’s rise, he proposes that the US lead the formation of a “democratic globalization organization.”

Conceptually, the idea of a DGO is to replace the WTO, rewrite the rules and gang up on China. This is perhaps appealing to functionaries in Washington but is neither realistic nor practical. Thanks to the success of the BRI, many of the countries that would need to align with the US have already developed deep economic ties with China and would not want to be part of such alliances.

Tom Friedman of The New York Times wrote after attending the Beijing Olympics in 2008, “When you see how much modern infrastructure has been built in China since 2001, under the banner of the Olympics, and you see how much infrastructure has been postponed in America since 2001, under the banner of the war on terrorism, it’s clear that the next seven years need to be devoted to nation-building in America.”

By the title of the book, Prestowitz implies that having the US on top is the natural order while being surpassed by China is not. It has been more than a decade since Friedman made his observation and we in the US have only gone backward on rebuilding our infrastructure. Isn’t it high time we started dealing with our internal challenges rather than thinking of ways to keep China down in order to stay “up”?

George Koo recently retired from a global advisory services firm where he advised clients on their China strategies and business operations. Educated at MIT, Stevens Institute and Santa Clara University, he is the founder and former managing director of International Strategic Alliances. He is currently a board member of Freschfield’s, a novel green building platform.